Frigate Birds: Vulnerability and Importance to the Maldives

Prepared by GPPAC South Asia members

Mr Hussain Rasheed (Sendi) (Lead Researcher) assisted by Dr Mariyam Shakeela

January 2026

Executive Summary

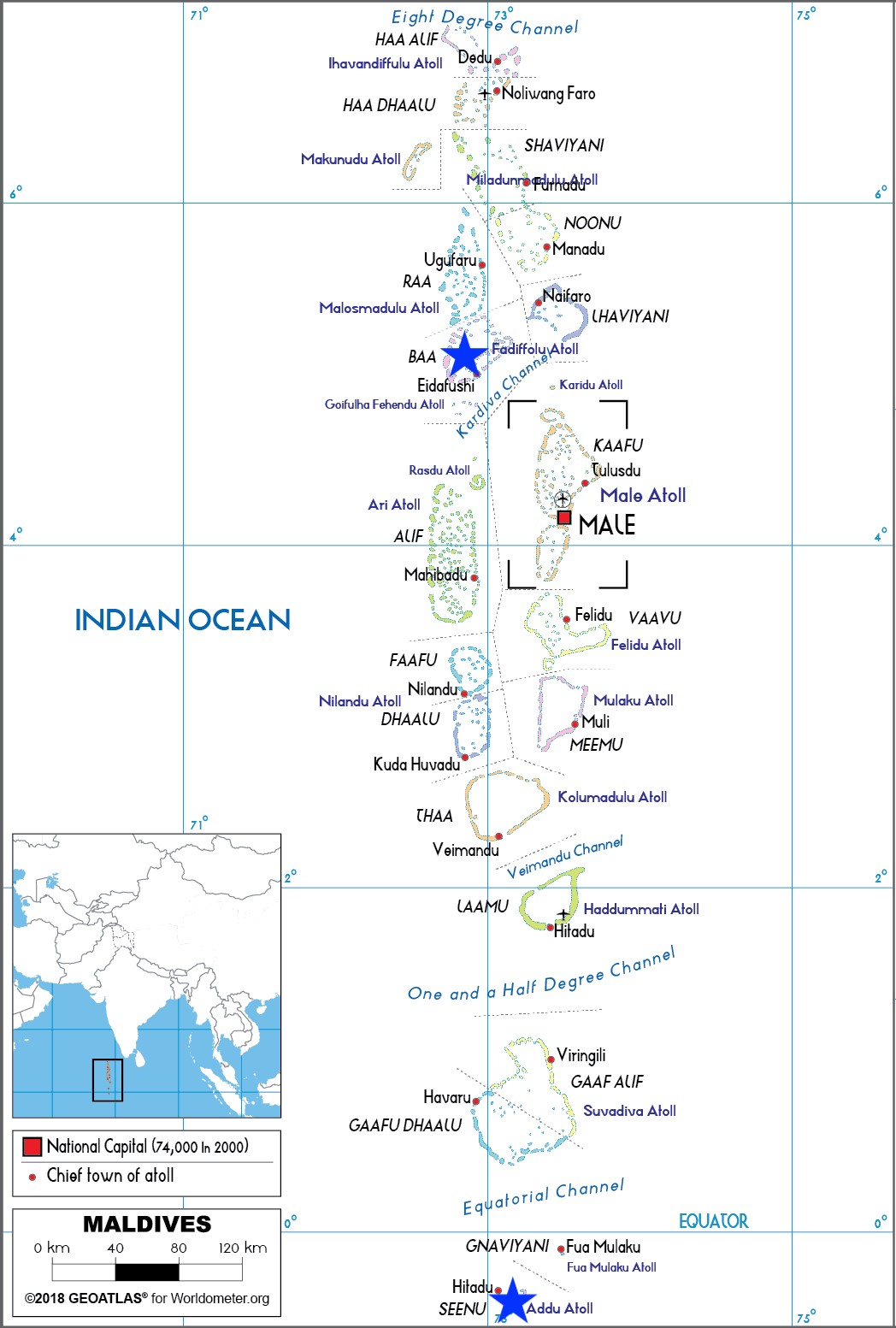

This report presents findings from a field visit to Olhugiri Island (Baa Atoll) undertaken to collect evidence of the disappearance of Frigate birds and draw attention to the dire need to apply the findings for conservation and management planning for Ga. Hithaidhoo (Frigate Bird Island) in North Huvadhoo Atoll, to preserve this important place. As Frigate birds have already abandoned Olhugiri in Baa Atoll for their roosting activities, Ga. Hithaidhoo is currently the last major communal Frigate bird roosting site in the Maldives. Prepared for the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC) South Asia network, the report situates the vulnerability of Frigate birds within a broader framework of environmental security, livelihoods, food systems, and long-term human security and social stability.

Frigate birds are a keystone indicator species for the Maldivian pole-and-line tuna fishery. Their presence has traditionally guided fishing communities to productive tuna grounds, embedding these seabirds deeply within local ecological knowledge and sustainable fishing practices. The documented disappearance of Frigate birds from Olhugiri reflects cumulative pressures, including coastal erosion, loss of large roosting trees, unregulated human access, tourism-related disturbance, and the absence of enforceable management frameworks.

Community consultations confirmed that Olhugiri once hosted thousands of Frigate birds, with their decline closely mirroring perceived reductions in regional fishing productivity. Field observations found no evidence of ongoing roosting activity, indicating complete site abandonment by disturbance-sensitive species.

These findings highlight urgent risks not only to biodiversity but also to fisheries sustainability, income security, and social resilience in an island nation where environmental degradation can amplify economic stress and social tension. The report underscores the critical importance of proactively protecting Ga. Hithaidhoo to prevent irreversible ecological loss and to safeguard the Maldives’ remaining Frigate bird population. It concludes with targeted recommendations for science-based management, enforcement, monitoring, and community co-management aligned with peacebuilding and conflict prevention objectives.

1. Introduction

This report has been prepared by the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (GPPAC) South Asia members to document emerging environmental risks in the Maldives and their intersections with livelihoods, food security, and long-term social stability. For a small island developing state such as the Maldives, environmental change is not a distant or abstract concern; it directly influences economic security, social cohesion, and the resilience of island communities whose lives and livelihoods are inseparable from the ocean.

Within this context, Frigate birds play a critical ecological and socio-economic role. They are a keystone indicator species closely linked to the Maldivian pole-and-line tuna fishery. For generations, fishers have relied on the flight patterns and congregation behaviour of Frigate birds to locate tuna schools, making these seabirds an integral part of traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable fishing practices.

The decline of Frigate bird populations, therefore, signals more than biodiversity loss. It reflects growing pressures on marine productivity, threats to income stability for fishing communities, and long-term risks to food security in a nation where fisheries remain a cornerstone of daily life and national identity.

As highly migratory seabirds, Frigate birds also connect the Maldives to wider regional and transoceanic ecological systems. Their seasonal movements and dependence on multiple habitats make them particularly sensitive to environmental disruption across borders. A detailed assessment of Frigate bird migration patterns and their implications for ecosystem health and fisheries sustainability has been discussed in a later section of this report, highlighting the regional and global dimensions of what may appear to be a local environmental issue.

This report further emphasises the urgent need to manage and conserve Ga. Hithaidhoo in North Huvadhoo Atoll, currently the last major communal Frigate bird roosting site in the Maldives.

2. Field Visit to Olhugiri Island, Baa Atoll

On 14 January 2026, a field visit was undertaken to Olhugiri Island to gather comparative ecological and community-based insights to support the development of a scientifically informed management plan for Ga. Hithaidhoo (Frigate Bird Island) in North Huvadhoo Atoll. Olhugiri was selected for its historical importance as one of only two known communal Frigate-bird roosting islands in the Maldives.

It is important to note that Frigate birds do not nest in the Maldives. They rely exclusively on specific uninhabited islands as communal roosting sites.

The field visit team included Mr Hussain Rasheed (Sendi), environmental and marine consultant, Mr Saddam Ali, Managing Director, SDM Ventures Pvt Ltd, and Hood – Media Coverage and Documentation (Flow). The primary objective of the visit was to collect field-based ecological observations and traditional community knowledge to support local organisations such as SDM Ventures in developing a management plan for Ga. Hithaidhoo, ensuring the long-term protection of critical Frigate bird habitat.

Upon arrival at Thulhaadhoo, the team met Mr Abdul Azeez, President of the B. Hithaadhoo Island Council, who facilitated discussions with community members possessing long-term observational knowledge of Frigate birds and traditional fishing practices. Key community insights were obtained from Mr Ahmed Hussein (local fisherman, B. Hithaadhoo) and Mr Idrees Hussain (local fisherman, B. Hithaadhoo).

3. Community Consultations

Olhugiri historically hosted thousands of Frigate birds (locally known as Hoara), particularly during the Iruvai season.

Frigate numbers were once so dense that residents could not remain on the beaches due to continuous droppings from birds gliding overhead. The birds typically began arriving around 3:00 pm, with numbers increasing steadily until the entire population roosted communally by evening.

Frigate birds are essential indicators for traditional tuna fishing, guiding fishers to productive fishing grounds. Birds feed primarily on flying fish driven to the surface by tuna, allowing fishers to locate tuna schools visually.

However, in recent years, large Lhos trees, the primary roosting trees, have largely disappeared due to severe coastal erosion. Community members could not determine a single cause of erosion, although they confirmed that many old and mature trees have been lost. Furthermore, overnight stays by resort groups, including the use of generators, were reported and believed to have disturbed roosting birds.

Community members expressed concern that the decline in Frigate bird populations mirrors a decline in regional fishing productivity.

Strong consensus emerged that replanting large Lhos trees is critical if Frigate birds are to return.

Other bird species historically observed include Lesser Noddies (kurangi), Valla, and other seabird species. Community members also recalled that the nearby island of Muthaafushi was once a major noddy roosting site. Following its lease for resort development, noddy populations have disappeared entirely, raising serious concerns regarding habitat loss and recovery potential.

The team also met with representatives of the Baa Atoll Biosphere Reserve (Eydhafushi) Head Office and held discussions with Mr Shafiu.

4. Field Observations

The marine environment, particularly the surrounding reefs were biologically rich and highly active. They showed the presence of large fish schools and diverse live coral communities. Dense vegetation suggested nutrient-rich terrestrial conditions and terrestrial vegetation.

Several native species were observed, including Funa, Midhili (Sea Almond), Magoo (Sea Lettuce), Dhiggaa, Dhivehi Ruh (Coconut), Maa Kashikeyo (Pandanus), Kuredhi, Kaani, and Nika.

Only a small number of Lhos trees were identified. Several very old Funa trees were observed, indicating intentional historical planting, as Funa wood was traditionally used in boat building.

No Frigate birds were observed. Additionally, there were no indirect indicators such as feathers, droppings, or long-term roosting signs. The absence of these indicators strongly suggests the site has been completely abandoned.

Numerous picnic and barbecue sites were observed across the island, suggesting the impact of human activity in these areas. There was a significant accumulation of plastic waste, including plastic bags, water bottles, instant noodle packaging, tuna cans, and biscuit wrappers. There was enough evidence to confirm frequent recreational use of the island.

The level of human activity observed at Olhugiri renders it unsuitable for disturbance-sensitive species such as Frigate birds.

5. Key Findings

Our community consultations and field observations indicate that the Frigate birds stopped roosting on Olhugiri around 2019. No studies have been conducted to determine why Frigate birds have abandoned the island.

Previous tracking data indicated migration between South Africa and Olhugiri; however, these records are currently unavailable.

Olhugiri lacks a dedicated and enforceable management plan. Existing management plans do not reference Frigate birds and focus primarily on the heron species. Additionally, routine ecological monitoring and assessments are also lacking. Currently, there is no framework to evaluate human-induced or natural habitat degradation in this area.

Unregulated access to the island, including coconut and pandanus harvesting, is further exacerbating the situation. Moreover, destructive practices, such as cutting large trees rather than climbing, result in the loss of critical roosting structures.

Although Lhos trees are present on many uninhabited islands, Frigate birds historically selected only two communal roosting islands in the Maldives. This suggests that roosting site selection depends on marine productivity as much as terrestrial vegetation.

Baa Atoll was historically rich in fisheries, coral reefs, and undisturbed islands. However, rapid tourism expansion has significantly increased disturbance levels.

The North Huvadhoo Atoll remains one of the Maldives’ most important commercial tuna fishing regions. In contrast to Olhugiri, Ga. Hithaidhoo, near Kolamaafushi, continues to serve as the last major Frigate-bird roosting hub in the Maldives, underscoring its national ecological importance.

6. Aligning Intersectionalities: Environmental Security, SDGs, and Livelihoods

The findings of this report align directly with the Maldives’ national commitments under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, climate change adaptation frameworks, and the emerging climate-security discourse. Protecting Frigate bird habitats is not a standalone conservation action, but a cross-cutting intervention that advances multiple SDGs while reducing climate-related risks to peace and stability.

SDG 13 Climate Action: Climate change acts as a threat multiplier in the Maldives, accelerating coastal erosion, habitat loss, and marine ecosystem degradation. The disappearance of Frigate birds from Olhugiri reflects climate-driven shoreline change combined with human pressure. Proactive conservation of Ga. Hithaidhoo contributes to climate adaptation by protecting ecosystem functions that support fisheries resilience, food systems, and community livelihoods.

SDG 14 Life Below Water: Frigate birds are closely linked to healthy tuna stocks and marine productivity. Their decline signals stress within pelagic ecosystems central to the Maldivian economy. Conserving Frigate bird roosting sites supports sustainable fisheries management, protects marine biodiversity, and reinforces the Maldives’ global leadership in pole-and-line tuna fisheries.

SDG 15 Life on Land: Although dependent on marine systems, Frigate birds rely on intact terrestrial habitats for communal roosting. The loss of large native roosting trees and the degradation of uninhabited islands undermine terrestrial biodiversity and ecological integrity. Habitat restoration and protection efforts directly advance SDG 15 targets on ecosystem conservation and the prevention of biodiversity loss.

SDG 2 Zero Hunger: Fisheries are a primary source of protein and income for Maldivian communities. By supporting tuna fisheries through the protection of ecological indicators such as Frigate birds, conservation actions contribute to food security and nutrition, particularly for the most vulnerable outer island communities, which are most at risk from climate shocks.

SDG 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth. Sustainable fisheries underpin employment, income stability, and economic resilience in the Maldives. Environmental degradation that disrupts traditional fishing knowledge and reduces fish availability threatens livelihoods. Protecting Frigate bird habitats supports long-term economic sustainability and decent work within the fisheries sector.

SDG 16 Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions. Environmental degradation can exacerbate social and economic stress, increasing the risk of localised conflict and instability. Strengthening governance over ecologically sensitive islands, enforcing management frameworks, and integrating community co-management mechanisms contribute to inclusive institutions, conflict prevention, and long-term peacebuilding.

7. Policy Recommendations

8. Conclusion

The Olhugiri field visit clearly demonstrates the combined effects of loss of large roosting trees, habitat degradation, unregulated human access, and tourism-related disturbances. These have resulted in the local disappearance of Frigate birds from the island.

Beyond biodiversity loss, these changes raise deeper concerns about environmental security. In the Maldivian context, declining indicator species such as Frigate birds signal weakening marine productivity, increasing pressure on fisheries-based livelihoods, and heightened vulnerability for island communities already facing climate-related stressors.

Protecting the remaining critical habitats is therefore not only a conservation priority but a preventative peacebuilding measure. Ga. Hithaidhoo represents the last opportunity to conserve a nationally significant ecological asset that supports fisheries sustainability, preserves traditional knowledge systems, and strengthens resilience in one of the Maldives’ most important fishing regions.

These findings highlight the urgent need for a robust, science-based, and enforceable management framework to protect Ga. Hithaidhoo (Frigate Bird Island).